Fatalism – the belief that things cannot be changed – is the greatest enemy of transformative leaders.

This article is based on the final talk given at the tenth Summer Institute of Authentic Leadership in Action (ALIA) in June 2010 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Over the Institute’s ten-year history, it has brought together systems-oriented tools and perspectives with the values and practices of authentic leadership, creating unique and powerful support for leaders, managers, and consultants from around the world. Since the Institute’s inception, Dr. Senge has been an advisor, friend and, on several occasions, guest speaker.

The Uganda Rural Development Training initiative discovered some powerful keys to overcoming fatalism and transforming the poorest area of the country into its most prosperous.

In 1985 or so, I met a man from Uganda, Mwalimu Musheshe, and he and a colleague were starting a program which eventually would be called Uganda Rural Development Training (URDT). They chose to work in the poorest region of what was a chaotic country at the time. In addition to these two men, there were one or two other people who were trying to raise money to support their efforts. Those supporters asked, “Why do you start in the poorest and the most backward part of the country?” Musheshe and his colleague said that it just seemed like the right place to start. In my first conversation with Musheshe I was really struck by his clarity. He said something that I have never forgotten which I first took to be a statement about Africa but have since seen to be much more general. He said,

The biggest limit on development in Africa is fatalism. When people do not believe they can alter their future, they do not believe they have efficacy in their life, and it doesn’t matter what you do to help them. Anything you do will just reinforce that belief. That’s why all aid efforts, no matter how enlightened, ultimately have within them the seeds of their own limitation.

Over the next three or four years, each year, we’d have a group of three or four young Ugandans who had come for about two months of training. We had a three-day leadership course; it used to be called Leadership and Mastery long ago. In fact, a lot of the ideas that found their way into The Fifth Discipline were incubated in that course, starting around 1979. The Ugandans would come every year, and they’d do that program, and they would do a lot of work in personal mastery and systems thinking. Each year, it would be about three people, typically mid- to late twenties. They were “field workers,” working in the villages in this region of Uganda, doing things like helping people dig better wells, establish better granaries, and construct better composting toilets – very basic improvements, but ones that people could undertake and continue themselves, where they did not need further outside assistance. They’d come for about two months and then go back, and of course, we didn’t see them after they went back. They were always wonderful young people, so much so that those of us leading those programs always felt we were really fortunate to be there when the Ugandans were attending

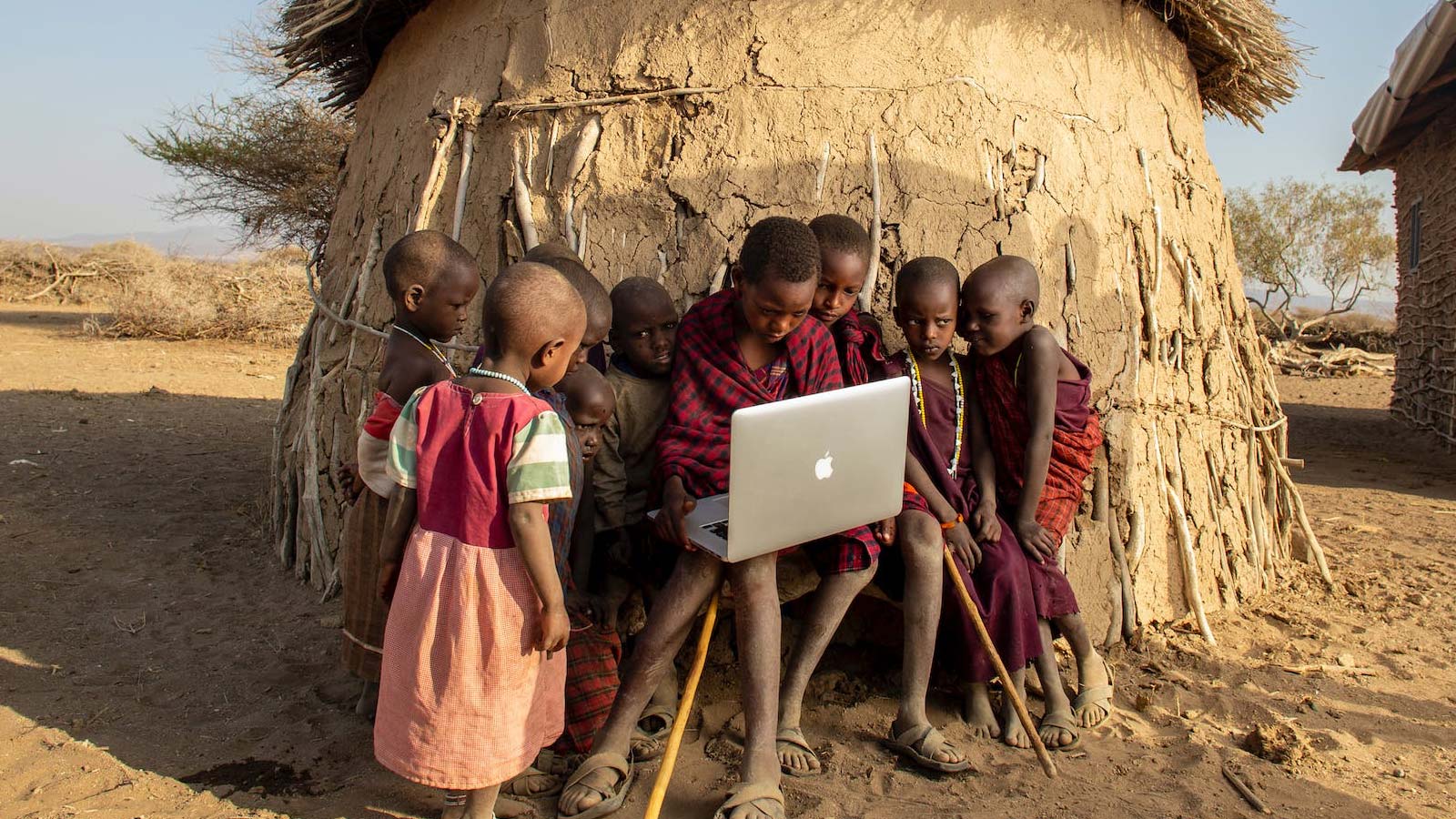

After a couple of years, they’d start to bring us photographs. I’ll never forget the first one I saw of someone who had written their vision on their hut. It was at that moment that I got the feeling that something was really happening. The clarity that the organizers had was shifting the underlying mindset and then doing things that would reinforce that shift in mindset. You don’t shift a mindset in the abstract. It’s in the day-to-day; it’s in the moment by moment; it’s in the doing; all learning is in the doing.

To make a long story short, today this is the most prosperous region of Uganda. URDT’s work has led to sustained economic development, microcredit, lots of small-enterprise creation, and a lot of emphasis on organic agriculture. In fact, Musheshe was recently asked by the President of Uganda to be a special advisor in their agriculture policy because URDT has been so successful at building a rural economy around organic agriculture. After 25 years, today URDT is probably one of the best success stories of rural development in central Africa.

“Leaders think and talk about the solutions. Followers think and talk about the problems.”

Brian Tracy

Motivational public speaker and self-development author.

About twelve or thirteen years ago, as a lot of these basics were starting to fall into place, and something was really happening in the whole region, they shifted and began a focus very specifically in one area. They decided that what was most important was the education of girls. How many of you have ever seen the video, The Girl Effect? It is quite remarkable and has been very influential around the world. When it first came out about two years ago it was one of the five most watched YouTube videos in the world for a good while. It’s remarkable. It probably packs more systems insight-per-minute, in its 2 minutes and 25 seconds, than anything I’ve yet seen.

Well, these people, without ever having seen this little video, were living it. In a poor country, most people have to pay for their children’s education, and when there’s not enough money to pay for all the kids’ educations, families generally pay for the boys’ education. That’s a fairly common pattern, so URDT started opening secondary schools for girls because typically girls will discontinue school around the age of ten, eleven or twelve. Three years ago they opened the first rural women’s university in Africa. Along the way, they came up with this brilliant model, what they call the “Two-Level Education Model.” Educate the girls, and the girls educate their parents. A lot of their parents don’t read, or don’t have a lot of the basic skills they need to be effective in a modern society. The girls call themselves “rural transformers.”

There’s nothing more powerful than two or three minutes of listening to one of these young girls talks – certainly, my words are very weak by comparison. So, URDT was one of the eight “exemplars” of systemic change we brought together in March, in Yucatan, Mexico. In the last two or three months, it’s become very apparent to me that miracles like URDT are happening all around us.

ROCA

Another one of the organizations that came to this meeting was another one I’ve known for about twenty years. It’s twenty-three or four years old, and it has been achieving similar miracles – this time in an inner city environment in this country. Roca is an organization composed mostly of former gang members who become what they call “youth workers.” These are young people, boys and girls, recruited off the streets, who in turn work with others on the streets to escape the street life of gangs, drugs and violence. They do this through an extraordinary process they have developed, primarily using Native American methods.

It is an interesting reflection on how learning is now occurring in this world of ours, that the primary method for the work that goes on with these young Cambodians and Vietnamese and Gabonians and Puerto Ricans comes from the Tlingit Indians in the Yukon, from whom Roca learned what they call “Peacekeeping Circles.” When everything is awry, when everything is out of balance, they form a circle. It’s quite an experience to sit down with a group like this; young people who are Latinos or Southeast Asians or Central Africans, the typical polyglot immigrant community you find in cities in North America, and start with “smudging,” circulating a bit of burning incense with cleansing smoke and watching these young people pray for guidance that their words and actions can serve their community. I cannot tell you how many young people I have gotten to know at Roca who would now be in jail or dead had it not been for their work.

Today, one of the most eloquent spokespeople for Roca – in an incredible juxtaposition of histories and images – is a retired Irish cop, the former police chief where Roca operates in Chelsea, Massachusetts. Chelsea is just across the harbor from Boston, so it’s literally about three miles from the financial district of Boston. It is a totally different universe, one that is typical in U.S. cities, where extreme poverty exists cheek-to-jowl with great wealth. I’ve gotten to know Frank, the retired Irish police chief. He says, “I’m really grateful that in the last ten years of my career I met Roca, because it was the first time in my life I felt like I could actually do something.

All my life, all I’ve been able to do is arrest people, to try to stop crime after the fact. Now for the first time, I feel like we’re dealing with the sources of violence in our communities.

So, there you see again Musheshe’s theme about fatalism. I believe most people in America don’t believe there is anything we can do about the violence and hopelessness of our inner cities. Speaking as a citizen of the United States, it is one of our dirty little secrets that, for over a decade, it’s been more likely that the young African-American man growing up in an American city will go to jail than to go on to any form of tertiary education. The largest growing segment of our jail population in America is young African-American women. The United States has around 5% of the world’s population and about 28% of the world’s prison inmates. And it’s a phenomenal business, much of which has been privatized over the past decade. So our meeting in Mexico also included Roca, which represents an antidote to this fatalism in the U.S., just as URDT does in Africa…

Stay up-to-date with our latest news:

Subscribe